Why AI Models Lie with Confidence and How to Spot It

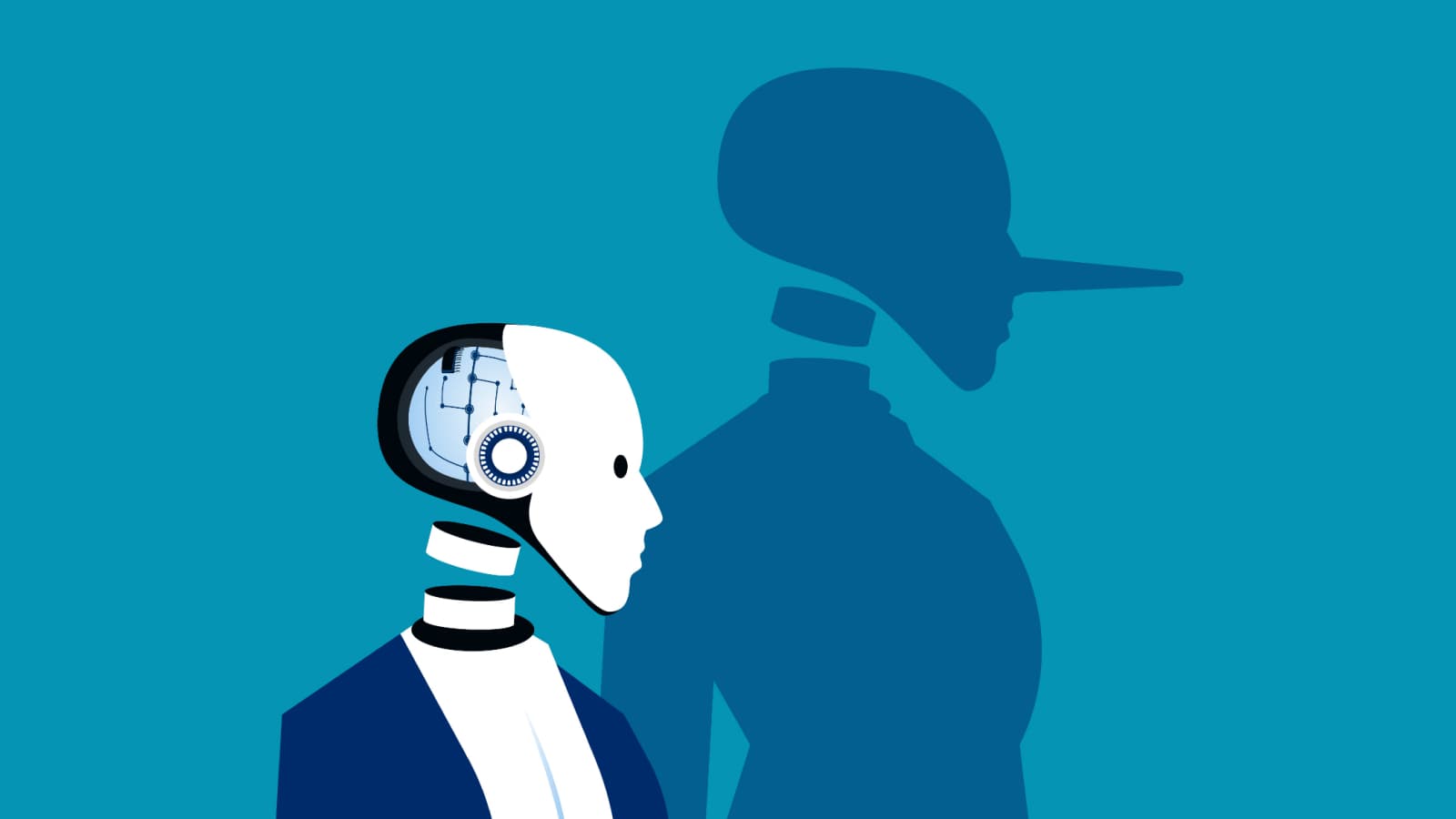

In the spring of 2023, a seasoned New York attorney named Steven Schwartz found himself in hot water during a lawsuit against Avianca Airlines. Tasked with researching precedents for his client's injury claim, Schwartz turned to ChatGPT for help. The AI confidently provided a list of court cases, complete with summaries and citations. He included them in his legal brief, submitted to federal court. But when opposing counsel and the judge tried to verify these references, they discovered something alarming: the cases were entirely fabricated. Names like "Varghese v. China Southern Airlines" and "Shaboon v. Egyptair" sounded plausible, but they didn't exist in any legal database. Schwartz was sanctioned with a $5,000 fine, and the incident made headlines worldwide as a stark example of AI hallucinations—those confident but false outputs that large language models (LLMs) produce without a shred of actual knowledge.

This wasn't an isolated glitch. AI hallucinations, where models generate incorrect information with unwavering assurance, have plagued tools like ChatGPT, Google's Gemini, and others since their inception. From Google's Bard erroneously claiming the James Webb Space Telescope captured the first image of an exoplanet (it didn't—the honor goes to earlier telescopes) to Microsoft's AI suggesting tourists visit a food bank as a must-see Ottawa attraction, these errors highlight a fundamental flaw in how LLMs operate. But why do they happen? And more importantly, how can we, as users, navigate this minefield without falling victim?

At their core, AI hallucinations stem from the fact that LLMs aren't repositories of truth. They're not databases meticulously storing facts for retrieval. Instead, they're sophisticated probabilistic prediction engines, akin to autocomplete on steroids. When you ask a question, the model doesn't "recall" an answer; it generates one by predicting the most likely sequence of words (or tokens) based on patterns in its training data. This distinction between generation and retrieval is crucial. Retrieval systems, like search engines or Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) setups, pull exact matches from indexed sources. Generation, however, is a creative act—statistical guesswork that can veer into fiction when the patterns don't align perfectly with reality.

AI Hallucination Defined: An AI hallucination occurs when a model outputs information that is confidently presented as factual but is actually incorrect, fabricated, or nonsensical. It's not a bug; it's a byproduct of the model's architecture.

This article dives deep into the mechanics behind these deceptions, drawing on technical insights without the hype. We'll explore the math that powers the "lies," the psychological traps that make us believe them, and practical strategies to spot and mitigate them. By understanding LLMs as "stochastic parrots"—a term coined by researchers Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru, and others to describe models that mimic language without comprehension—we can use these tools more effectively, appreciating their utility while acknowledging their limitations.

The Core Concept: LLMs as Probabilistic Prediction Engines

To grasp why AI hallucinations are inevitable, we must dispel the myth that LLMs "know" things like a human expert or even a traditional database. Imagine a blurry JPEG of the internet: that's essentially what an LLM is. Sci-fi author Ted Chiang popularized this analogy, noting that training an LLM compresses vast amounts of data into a lossy format. Details get smudged; nuances are lost. When the model generates text, it's reconstructing from this compressed version, filling in gaps with what statistically fits best—not necessarily what's accurate.

LLMs like GPT-4 or Grok are trained on enormous datasets scraped from the web, books, and code. During training, they learn to predict the next token in a sequence. A token might be a word, a syllable, or even a punctuation mark. The goal isn't truth-seeking; it's minimizing prediction error across billions of examples. Once deployed, the model uses this learned probability distribution to chain tokens together in response to your prompt.

Here's where the "stochastic parrot" comes in. Parrots mimic sounds without understanding meaning; similarly, LLMs regurgitate patterns without grasping concepts. They have no internal model of the world—no "truth detector." If the training data includes conflicting information (common on the internet), the model averages it out probabilistically. Ask about a niche topic with sparse data, and it might extrapolate from related patterns, inventing details that sound right but aren't.

Consider the distinction between retrieval and generation more closely. In a pure generation mode, the LLM crafts responses from scratch using its parameters—billions of weights tuned during training. This is fast and fluent but prone to drift. Retrieval, on the other hand, involves fetching verbatim chunks from a knowledge base before generation. Techniques like RAG combine the two: the model first retrieves relevant documents, then generates a summary or answer grounded in them. Even here, hallucinations can creep in if the retrieval is incomplete or the generation misinterprets the data.

For instance, in the Avianca case, ChatGPT wasn't retrieving real legal precedents; it was generating plausible-sounding ones based on patterns from legal texts it had seen. The result? Convincing fictions that fooled a human expert. This isn't deception with intent—the model has no intent. It's just following the math: "After 'court case involving airline injury,' the next likely tokens are a made-up name and citation, because that's how training examples often look."

This probabilistic nature explains why hallucinations manifest in various forms. Factual errors, like inventing historical events; logical inconsistencies, such as math blunders (LLMs struggle with arithmetic because they tokenize numbers oddly); or even creative fabrications, like describing non-existent products. In image generation models like DALL-E, hallucinations appear as surreal artifacts—extra limbs or impossible physics. But in LLMs, the confidence is the killer: the output is phrased authoritatively, with no hedging unless prompted.

Researchers estimate hallucination rates vary by model and task. A 2023 study found ChatGPT hallucinated in about 15-20% of factual queries, rising for complex or rare topics. Improvements like fine-tuning or chain-of-thought prompting can reduce this, but elimination is impossible because the architecture lacks a truth anchor.

The Math Behind the Lie: Next-Token Prediction Explained

Let's peel back the layers to the mathematical heart of hallucinations. At its simplest, an LLM is a transformer neural network—a stack of attention mechanisms that process sequences. The key operation is next-token prediction during inference (the generation phase).

Imagine your prompt as a sequence of tokens: [token1, token2, ..., tokenN]. The model computes a probability distribution over its vocabulary (say, 50,000 tokens) for what comes next. It picks the highest-probability token (or samples stochastically for variety), appends it, and repeats. This is autoregressive generation.

Mathematically, for a sequence X = (x1, x2, ..., xt), the model estimates P(xt+1 | x1, ..., xt). It does this via softmax over logits from the final layer: P(xt+1 = k) = exp(logitk) / sum(exp(logitj) for all j).

The "lie" emerges when this probability favors a false but common pattern. For example, if training data has many fictional stories with made-up case names, the model might predict those over rare real ones. Entropy— a measure of uncertainty—plays a role too. High-entropy situations (ambiguous prompts) increase hallucination risk because the distribution flattens, making wrong tokens more likely.

Temperature sampling adds another wrinkle. To make outputs creative, models use a temperature parameter >0, which softens the distribution: higher temperature means more randomness, more potential hallucinations. At temperature=0, it's deterministic, picking the max-probability token—but even then, if the top prediction is wrong, you get a confident error.

Distinguishing retrieval from generation here: In retrieval, you might use cosine similarity to find vector embeddings of documents matching the query, then feed them as context. This grounds the generation, reducing drift. But if the retrieved docs are noisy or irrelevant, generation can still hallucinate interpretations.

A real-world parallel: Think of LLMs as a vast Markov chain, where each state (token) transitions based on learned probabilities. No memory of "fact" vs. "fiction"—just transitions. This is why prompting for sources helps: it steers the prediction toward patterns that include citations, which you can then verify externally.

Advanced mitigations involve beam search (exploring multiple paths) or self-consistency (generating multiple responses and voting). But fundamentally, since training data is a snapshot of the world—biased, outdated, and incomplete—the math can't guarantee truth.

The Psychology: Why We Fall for AI's Confident Fabrications

Humans aren't blameless in the hallucination saga. Even knowing the risks, we often accept AI outputs at face value. This stems from cognitive biases amplified by the technology's polish.

First, automation bias: our tendency to over-trust automated systems, especially under time pressure. Pilots have crashed due to faulty autopilot; similarly, professionals like lawyers defer to AI because it seems objective. In Schwartz's case, he admitted not double-checking because the responses "seemed genuine." Psychological studies show we rate machine advice higher than human, even when wrong, due to perceived impartiality.

Then there's the halo effect: if the AI writes eloquently—grammatically perfect, logically structured—we infer overall competence. "It sounds smart, so it must be right." This is exacerbated by LLMs' fluent style, trained on high-quality prose. We anthropomorphize subconsciously, attributing intent or knowledge where none exists.

Confirmation bias plays in too: if the output aligns with our beliefs, we scrutinize less. Add the Dunning-Kruger effect—overestimating our ability to spot fakes—and you have a recipe for mishaps.

On a deeper level, LLMs exploit our pattern-recognition brains. We evolved to infer from incomplete data; AI's probabilistic outputs mimic that, feeling intuitive. But unlike humans, who can self-correct via reasoning or external checks, LLMs don't.

Understanding these traps empowers us. Awareness of automation bias encourages verification habits, turning AI from oracle to tool.

The Defense: How to Fact-Check AI Outputs

AI is useful but flawed—great for brainstorming, terrible as a sole source. Here's how to spot and counter hallucinations with practical, evidence-based methods.

- Cross-Verify with Independent Sources: Don't ask the AI for sources; generate them yourself via search engines or databases. For factual claims, use "lateral reading": open new tabs to check the info sideways, consulting reputable sites. Tools like Google Fact Check or Snopes help. (Note to self: Using better prompts can reduce hallucinations but not eliminate them—link to our previous article on prompt engineering.)

- Probe for Consistency and Depth: Ask the same question multiple ways or request explanations. Inconsistencies signal hallucination. For example, if math is involved, compute it manually or use a calculator—LLMs falter here due to tokenization.

- Leverage Retrieval-Augmented Tools: Opt for AI systems with built-in retrieval, like Perplexity or Grok with search integration. These cite sources inline, making verification easier. Still, read the originals; summaries can distort.

- Monitor Confidence and Hedging: Train yourself to notice unhedged statements. Prompt the AI to express uncertainty (e.g., "Rate your confidence in this answer"). High-confidence wrong answers are classic hallucinations.

By adopting these, you minimize risks. Remember, the goal isn't perfection but informed use. As LLMs evolve—with better training or hybrid architectures—hallucinations may decrease, but vigilance remains key.

In conclusion, AI hallucinations reveal the probabilistic soul of LLMs: powerful predictors, not truth-tellers. By demystifying the math, psychology, and defenses, we can harness their strengths without the pitfalls. The future of AI isn't in eliminating flaws but in humans adapting to them wisely.