Beyond Algorithms: Teaching AI Real-World Skills

When people talk about AI, the conversation often veers into science fiction territory—killer robots and superintelligence. But that narrative misses the point. The real story of Applied Artificial Intelligence isn't about creating a new life form; it's about building tools that solve meaningful problems for real people. I’ve seen this firsthand, designing AI to help wind farms generate more sustainable energy, factories cut their emissions, and buildings operate more efficiently.

The key is shifting our mindset from programming algorithms to teaching machines. By creating a framework for teaching AI specific skills and strategies, we can tackle some of our most pressing challenges. This isn't about tweaking neural networks; it's about a practical Machine Teaching Methodology that empowers us to build smarter, more adaptable systems.

The Limits of Rigid Automation

Many businesses rely on automation, but there's a huge difference between an automated system and an autonomous one. I once consulted for a company that used a robotic arm to move freshly-cut cell phone cases from a CNC machine to a conveyor belt. The system was automated, meaning its controller was hand-programmed to move from one fixed point to another.

It worked perfectly, but only under perfect conditions. If a phone case was slightly wider than expected or sitting in its fixture at a slightly different angle, the arm would fail. It would either miss the part completely or drop it mid-transfer. The automation was brittle because it couldn't adapt.

This is a classic case where a more advanced Autonomous AI System Design is needed. Instead of following a rigid script, an autonomous system perceives its environment and adapts. It could practice grasping cases of various widths and orientations, learning to succeed in a much wider range of real-world scenarios.

Adapting When the World Changes

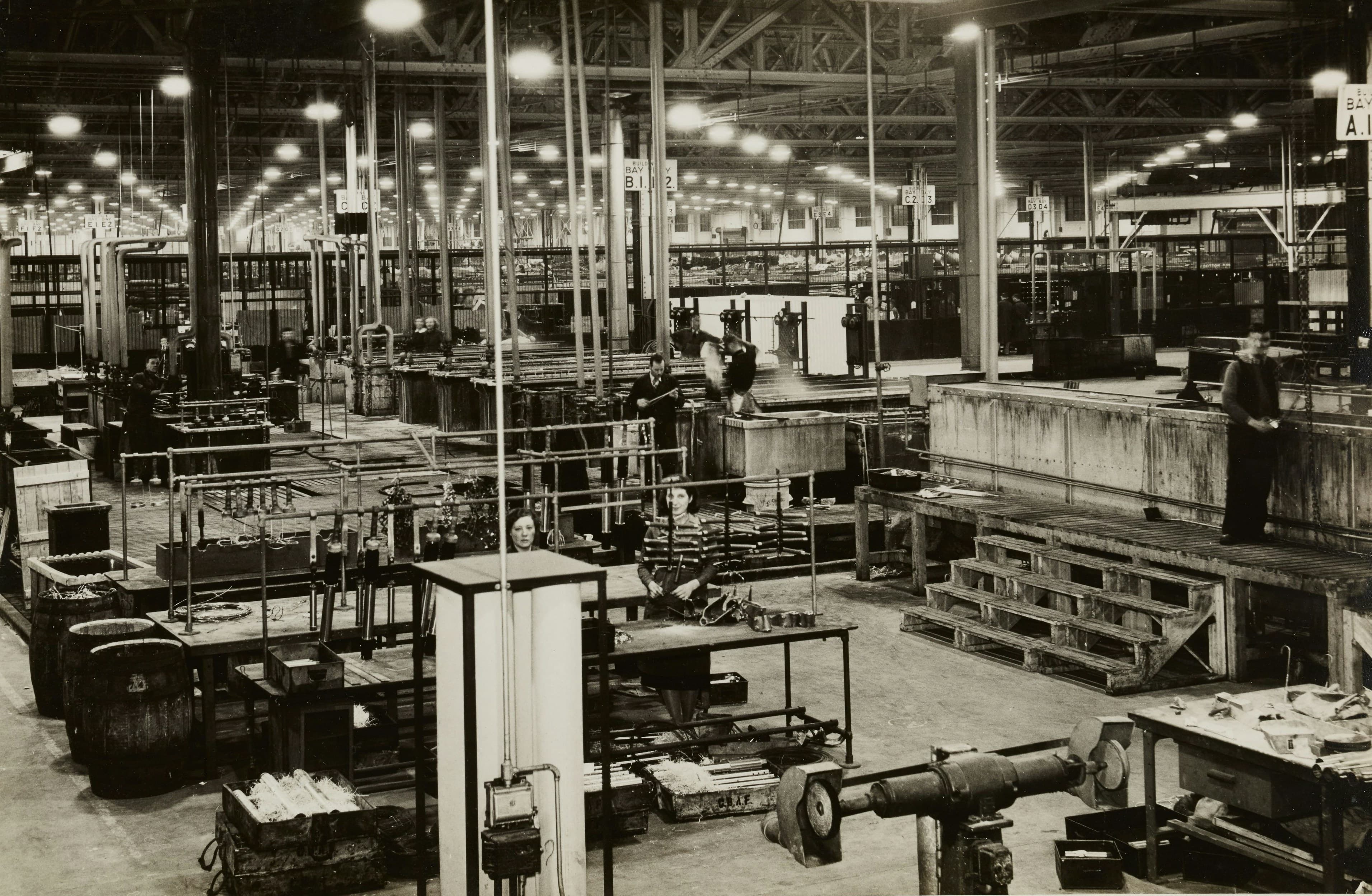

That need for adaptability is showing up everywhere. I was once asked to visit a massive steel mill in Indiana to see how AI could help their operation. After touring a facility that could fit several skyscrapers inside, I spoke with the operators who manage the final stage of the process: galvanizing, where a strip of steel gets a protective zinc coating.

Their job used to be relatively straightforward. They primarily produced steel of a standard thickness and width for the big three US auto manufacturers. But the market had changed. Now, they were fielding orders from countless customers for all kinds of steel—wide and thin for construction, narrow and thick for heating ducts. The operators were struggling to keep the zinc coating uniform across all these new variations.

Their existing systems, both human and automated, were built for a predictable world. As their business environment changed, they needed a new approach to industrial process optimization. Autonomous AI offered a solution by learning to manage the coating process effectively across a constantly shifting variety of products.

The Problem with Data Science Colonialism

As companies turn to AI for answers, they often make a critical mistake: they focus on algorithms instead of solutions. I saw this with a major US rental car company that needed help scheduling the daily delivery of cars between its city locations. On paper, this looks like the "Vehicle Routing Problem," a classic logistics puzzle with well-known optimization algorithms designed to find the shortest possible routes.

So why were they still using human schedulers? Because the real world is messy. An algorithm like Dijkstra’s might find the shortest distance between two points, but it doesn't account for traffic, which is the single biggest factor in a major city. A route that’s shorter in miles can take much longer during rush hour. Real human schedulers know this; they have an intuitive feel for a city’s traffic patterns.

This highlights a dangerous trend I call "data science colonialism." It’s the practice of using data alone to dictate a solution, ignoring decades of hands-on human experience and the physical laws governing a process. I’ve seen data scientists argue with process experts at a nickel mine, insisting their models were superior to the operators' hard-won knowledge.

An executive at a manufacturing company once told me how refreshing it was that I wanted to learn from his team. He’d had countless firms tell him, "Just give us your data, and we'll build you an AI." He knew, and I agree, that you can't ignore human expertise and expect to build a system that works safely and effectively on expensive, mission-critical equipment. The most effective solutions come from strong Human-AI Collaboration Frameworks, where technology enhances expertise, not dismisses it.

Capturing Expertise Before It Walks Out the Door

That human expertise is a company's most valuable asset, and right now, it’s disappearing. Experts are retiring at an alarming rate, taking decades of knowledge with them. At a chemical company that produces plastic film, it takes an operator seven years of training before they’re qualified to "call the shots" in the control room. When that person retires, how do you replace that experience?

This is where Applied Artificial Intelligence can serve as a bridge. In Navasota, Texas, I worked with a machinist named David, a 35-year veteran in his field. He could get cutting jobs done faster and at a higher quality than any automated software because he’d internalized the unique quirks of over 40 different machines, some brand new and some decades old.

His company wanted to use AI as a training tool. The vision was to create a system that could sit alongside a new hire and augment their skills, not replace them. By interviewing experts like David, we can identify the core skills and strategies they use and then design an AI to practice those same skills. This Machine Teaching Methodology allows us to package expertise into neat, transferable units.

Skills Are Simple to Teach, but Hard to Master

The beautiful thing about expertise is that it often breaks down into surprisingly simple strategies. I worked with SCG Chemicals, a company that has been manufacturing plastic for a century. When I asked how they train new operators to control the complex chemical reactors, the answer was concise. They teach two primary strategies in a specific order:

- First, add ingredients to get the plastic's density into the target range, ignoring other measurements.

- Once the density is right, switch strategies. Now, ignore the density and add ingredients until the melting point meets the product specification.

It works every time. The strategies are easy to explain, but mastering them takes years of practice. An operator needs to learn how much reagent to add based on the specific type of plastic, the catalyst being used, and even the ambient temperature.

It’s just like baking. Your dad might teach you a family recipe with two main steps: mix the first set of ingredients until the dough feels sticky, then add the second set and knead until it's firm. The recipe gives you a rigid guide, but an expert baker knows to adjust based on the humidity in the air. Over time, they stop needing the recipe and develop an intuition. A proper Autonomous AI System Design can be taught these foundational strategies and then practice them across thousands of scenarios to develop that same nuanced intuition.

This approach flips the conventional wisdom on its head. Instead of simplifying a problem until an algorithm can solve it, we should add nuance to our decision-making capabilities until they can solve the realistic problem well.

A Tool for Solving the Right Problems

When you build systems this way, you can start tackling bigger issues. About 50% of the energy used in buildings goes to HVAC systems. At Microsoft's campus, we used this approach to design an AI that makes supervisory decisions for the heating and cooling systems based on real-time factors like occupancy and outdoor temperature. The new system cut energy usage by about 15%.

This is more than just industrial process optimization; it's a tool for positive change. However, access to these powerful technologies is deeply unequal. That's why I'm passionate about democratizing this knowledge. I’ve started teaching these concepts to underrepresented students, hoping to put these tools into the hands of those who can use them to advance their communities and solve problems they care about.

The goal is to build better Human-AI Collaboration Frameworks, where an operator can walk into a control room with an AI they helped design, or a student can learn a complex skill by practicing with an AI they taught. The progress is real, and it’s an invitation for all of us to use our skills to build something truly useful.