Metacreativity: How AI Reshapes Human Work and Creative Identity

Imagine a future where the act of creation, once solely human, is increasingly shared with intelligent machines. This isn't just science fiction; it's the core idea behind metacreativity. As an evolving concept, metacreativity signifies the next major cultural shift, moving us towards a 'posthuman' era where human production—including creative output—can be delegated to non-human systems. These systems can be anything from sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) to learning machine learning (ML) algorithms, or even vast, interconnected digital processes. While it certainly encompasses current AI chatgpt capabilities and advanced bots, this definition ultimately extends beyond our present understanding of AI.

Specifically for emerging intelligent technology, metacreativity means that non-human entities, agentic AI systems, and actors are able "to learn" in order to produce something through what is commonly considered a creative process. Right now, this stage involves delegating significant portions of creative work to self-training algorithmic machines. As artificial intelligence takes on these labor-intensive, repetitive tasks, it frees humans to concentrate on bigger picture issues that shape creativity. Yet, this shift also forces humanity to deeply question its own identity and unique role in a world where machines can "create."

Unpacking the Paradigms of Metacreativity

Metacreativity isn't an isolated phenomenon; it operates across cultures through various interconnected frameworks, or paradigms. We can think of these as two main types: interstitial and meta. Interstitial paradigms are often overlooked or taken for granted, but they form the essential foundation for the more commonly recognized meta paradigms that shape our daily reality. Together, they create a complex cognitive map illustrating their tight interconnectivity.

Interstitial Paradigms: The Unseen Foundations

These foundational paradigms, while not always consciously perceived, are crucial for the emergence of all other recognized cultural concepts. They make possible the emergence of meta paradigms, which are generally more recognizable across cultures. Here’s a brief look at some key interstitial paradigms and how they enable modern life:

- Labor: This is about human activity and the domestication of resources. Its continuous optimization, driven by innovation, leads to specialization, allowing us to view materials as interchangeable parts.

- Modularity: This concept focuses on using discrete, swappable pieces or elements in production, interaction, and communication. It develops alongside the specialization and automation of labor.

- Memory: Our understanding of memory isn't static. It's constantly being reconstructed, shaping our perception of the past, present, and future. Modularity further supports how we access and conceptualize information, especially with external memory aids.

- Technology: This refers to the material and conceptual tools that reshape human actions, forming a modularized global society. Technology acts as a binder, making all paradigms more efficient.

- Compression: This is our drive for efficiency, often tied to convenience and innovation, and strongly influenced by capitalism, which fuels the development of artificial intelligence. It optimizes processes, enabling simulation.

- Simulation: This paradigm allows for the modeling of possible scenarios, supporting labor optimization through technological innovation. Simulation also helps produce self-fulfilling situations that challenge our understanding of reality, sometimes with disruptive consequences.

- Environs: This addresses our relationship with the environment. The cumulative effect of the other interstitial paradigms has led to severe environmental consequences, making critical reflection on their implications on cultural production essential.

These interstitial paradigms are deeply interwoven throughout culture, supporting the meta paradigms that are more visible and often institutionalized in society. They may go unnoticed but are integral for complex cultures to function and thrive.

Meta Paradigms: Shaping Our Daily Reality

Meta paradigms are the concepts we easily recognize, defining our everyday experiences. They provide concrete ways to share information, communicate, and explore creativity, all supported by the underlying interstitial paradigms. Examples include:

- Art & Music: Integral to human cultural evolution since ancient times, these remain foundational to our cultural expression.

- Media: While art and music have always existed, media became a distinct paradigm with the advent of mechanical reproduction in the 19th century.

- Culture: Dating back to early human history, culture encompasses art and music and provides the context through which we understand the world.

- History: Often seen as an overarching paradigm, history is best evaluated through specific cultural contexts, as culture profoundly shapes how history itself is written and interpreted.

These meta paradigms act like cultural modules, influencing each other and leveraging interstitial paradigms. Their interconnectedness allows principles of metacreativity to emerge, often with the support of AI aesthetics.

Labor's Evolution: From Fields to Algorithms

Labor, often used interchangeably with "work," fundamentally refers to doing something to live, usually involving physical action or producing something tangible. Its evolution is crucial to understanding metacreativity and the role of AI in work.

Historically, labor began with agriculture, leading to complex societal hierarchies. With the rise of mercantilism and capitalism, particularly after European exploration of the Americas, new economic structures emerged. The 18th and 19th centuries brought the industrial era, marked by factories and regional infrastructure. This was followed by the post-industrial period, focusing on service-based economies, which then gave way to the information age, heavily reliant on knowledge and data. This chronological development can be reframed through four interconnected layers of production:

The Expansional Layer

In this foundational layer, material and cultural production are established. It defines territory and explores ways to expand labor using natural and human resources. Early societies saw work delegation and hierarchical compartmentalization. Agriculture, for instance, became a specialized, complex form of food production that continuously sought efficiency through growth. As historian Fernand Braudel noted, human labor limits became clear as demand for goods rose, prompting early technological innovations like the plow, powered by animals. These animals became extensions of human brute force for efficiency. Human strength, it was realized, lay not in physical prowess, but in the conception of ideas and inventions.

This layer isn't confined to the past; it thrives today in speculative innovation. Projects like moon colonization or building off-world settlements on Mars still fall under the expansional layer, often relying on machine learning algorithms to assess feasibility and drive investments.

The Optimizational Layer

This layer brings specialization and efficiency, characteristic of the industrial and post-industrial periods. The factory, epitomized by Henry Ford's assembly line, streamlined repetitive labor by assigning a single, specific function to each person. This model, which reduced tasks to carefully synchronized repetitions, became the standard for advanced industrialization. While factories became cornerstones of capitalism, they also drew criticism for the dehumanizing, mind-numbing nature of repetitive work, famously depicted in Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times.

Today, this layer continues to evolve significantly with AI in work. Computers, integrated with machines, allow robots to perform most factory tasks. Beyond manufacturing, we see this optimization in everyday conveniences like washing machines, online banking, and automated bill payments, where human interaction is minimal or absent. Generative AI for business is now extending this optimization to more complex, cognitive tasks.

The Modular Layer

Here, streamlined, specialized tasks define the service industry. As machines took over repetitive assembly work in factories, a shift towards a service-based economy began, setting the stage for the informational layer. The traditional "blue collar" (manual labor) and "white collar" (office work) distinction, once tied to social class, became more porous.

Research shows that many office and service jobs, particularly data entry roles, are vulnerable to computer automation. For instance, AI and Machine Learning (ML) algorithms now largely replace bank tellers and loan officers, approving small loans in minutes. Jobs requiring complex, unique decision-making, like carpentry or plumbing, remain less susceptible to AI in work due to their reliance on practical, in-depth human knowledge. The rise of automation here is driven by the complexity of problem-solving rather than strict job labels, underscoring the growing importance of the informational layer.

The Informational Layer

This layer makes human production more efficient by enhancing other layers with targeted data and information, while also treating information itself as a valuable commodity. Its prominence surged with the rise of computers, first in military and industrial contexts, then in commercial and daily professional use. From office writing and internet communication to smartphones and computer-generated imagery (CGI), the informational layer supports new types of production that blend "blue collar" and "white collar" tasks.

This has led to highly skilled IT jobs, combining advanced degrees with hands-on hardware and software development for network infrastructures. New, often ambiguous categories of "gray collar" labor have also emerged, encompassing remote customer service for transnational corporations, forming what's often referred to as the "gig economy." Sociologist McKenzie Wark identifies two new classes defined by this layer: the "vector class," controlling information flow (like capitalists control production), and the "hacker class," capable of creating new kinds of objects, subjects, and relationships that question property itself. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly highlighted this shift, showing how remote-capable informational labor was resilient, while many service and manual jobs faced significant disruption. This demonstrates how generative ai and other information technologies are redefining class structures, moving global culture into a hybridized information economy.

The Automation of Creation: Labor, Art, and Remix

Automation, far from being a modern invention (it dates back to ancient tools like the Antikythera Mechanism), found its formal footing with figures like Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, who envisioned automating repetitive mathematical processes for an industrialized society. This drive to automate "mindless" labor underpins much of current AI innovation and, crucially, frames creativity as humanity's most valued asset.

This systematic analysis of the world, propelled by industrialization, aimed to make processes more efficient. Karl Marx's critique of factories highlighted how streamlined production could dehumanize workers, treating them as mere subjects of labor. Later, Herman Hollerith's punch-card technology for the US census foreshadowed the computing giants like IBM and Apple, which would bring computers into corporate and personal use, further automating information processing.

This era also saw a systematic approach to understanding humans themselves, moving from Freud's psychoanalysis to cognitive psychology, laying groundwork for posthumanism—a field that explores how humans are deeply intertwined with the planet. The lesson: we must be wary of reducing the history of technology to simplistic materialism, as this can lead to exploitative systems, echoing historical injustices like slavery and contributing to modern socio-economic inequalities, as the Black Lives Matter movement highlights. The rapid push to automate basic tasks is now extending to the automation of creativity itself.

Art and Delegated Creativity

Artists have long challenged the notion of intense manual labor being central to art. Marcel Duchamp's "readymades" in the 1910s, seemingly effortless assemblages, were in fact carefully conceived, emphasizing the idea behind the art over its physical creation. This approach influenced later conceptual artists of the 1970s, like Hans Haacke and Sol LeWitt, who focused on dematerializing the art object, often producing instructions or philosophical treatises instead of physical works. Their methods often functioned like algorithms: they developed a set of rules to abide by in order to produce the work, directly linking art practice to intellectual labor.

Today, the art world generally accepts that artistic practice is driven by an idea or theme, even in labor-intensive production. However, ML automation complicates our understanding of originality when creative processes are delegated to computer algorithms. This ease of delegation is closely linked to principles of remix culture, which gained global traction with the internet.

Remix Culture: The Algorithm of Selectivity

Remix culture has often been stigmatized by the popular assumption that originality is exclusive to humans and emerges from hands-on work. Critics like Henry Rollins dismiss electronic music for its use of sampling, viewing it as lacking "real" skill or labor. Even those who acknowledge remix creativity, like Kirby Ferguson, note that with modern AI tools, anyone can remix and distribute content globally without needing expensive equipment or even specialized skills. He stated, "You don't need expensive tools, you don't need a distributor, you don't even need skills."

This highlights how labor has historically legitimized creative processes. Sampling, with its seemingly effortless execution, challenged traditional notions of labor and talent. It questioned the need for instrumental mastery, reducing music creation to "pushing buttons." Regardless of the stigma, sampling profoundly challenged originality. It compressed labor into a modular method, optimizing executable actions through depersonalization—no human needing to play an instrument, just repurpose recorded sounds.

Sampling, as a foundational property of remix, enabled the dissemination of ideas and the creation of new forms based on a selective process. It subverted physical labor into an "analogical algorithm" performed by a machine, serving intellectual labor and exposing the depersonalization of work into executable abstraction. This intense labor has always been linked to creativity, often through constant experimentation. In music, DJing and sampling transformed the studio into an instrument, making creation more efficient by focusing on ideas. Producers could treat entire pre-recorded melodies as basic musical elements.

While sampling creates "meta-resources" (databases of sounds), critics often fail to grasp its complexity as a selective creative process. This technological implementation allows creativity to gain critical distance from its production, a process now fully entrenched with the emergence of machine learning in art, music, literature, and culture at large. Projects utilizing neural network in AI and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), such as "This Person Does Not Exist" (producing realistic portraits of non-existent people) or AICAN (creating paintings mimicking famous artists), demonstrate how generative AI models can produce images indistinguishable from human work without contextual information.

The Future of Labor and Identity with Artificial Intelligence

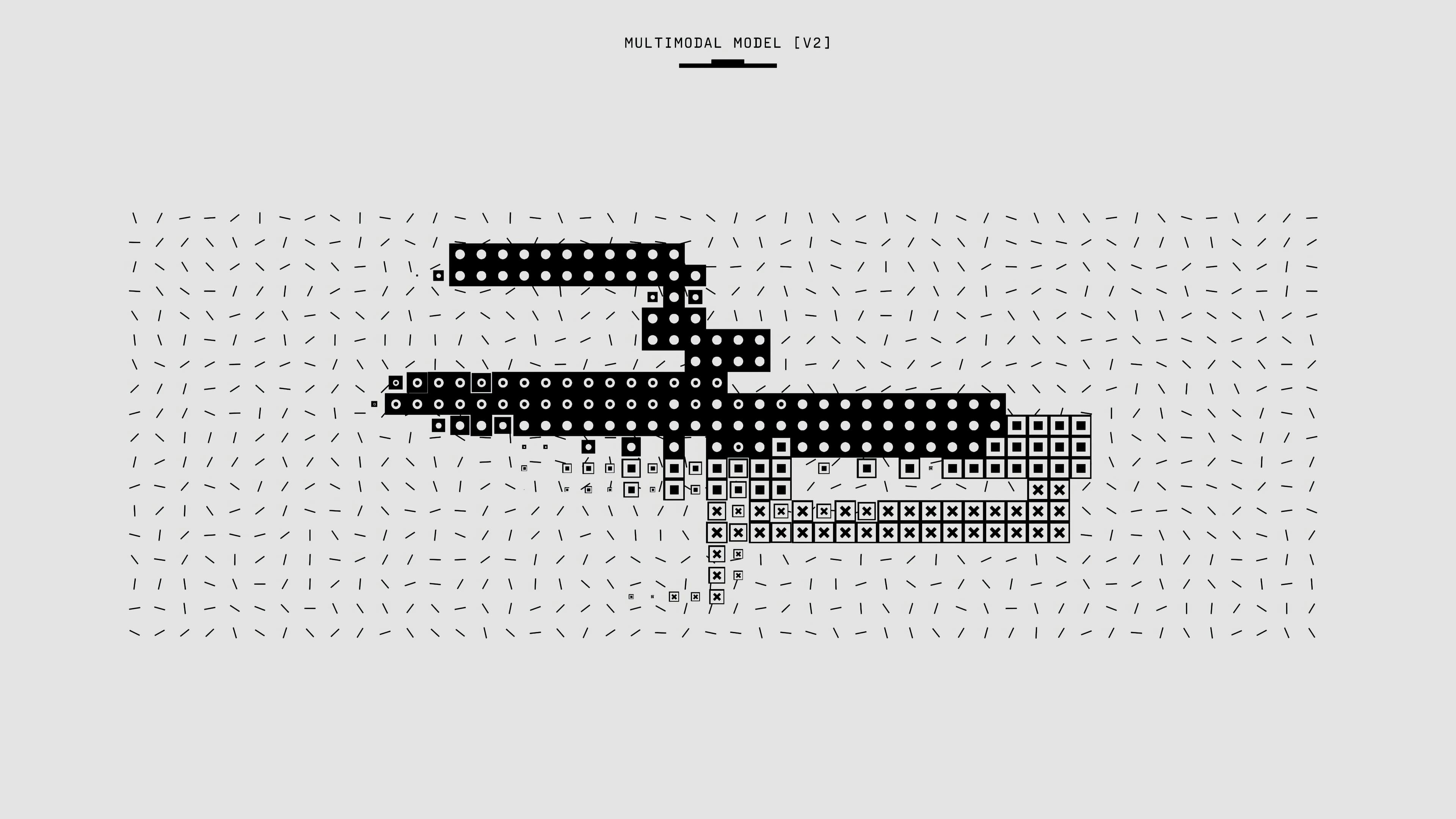

We return to the four layers of production—expansional, optimizational, modular, and informational—which are now symbiotically optimized through relentless investment in delegating work. All layers remain active and interdependent, forming the infrastructure of our current era. Metacreativity arises from a surplus of innovation within the informational layer, merging delegated decision-making with specialized actions, pushing the normalization of delegating even creative labor.

In digital art and media, Adobe's integration of ML across its programs is a prime example. Gavin Miller, Head of Adobe Research, explains how AI tools help designers focus on creativity: features like single-click object selection, or even automatic identification of dominant objects, aim to free users from technical complexities. He discusses how "using neural nets for actually doing a great job, say, with a single click, or even in the case of well-known categories, such as people or animals, with no clicks, where you just say 'select the object,' and it just knows the dominant object is a person in the middle of a photograph; those kinds of things are really valuable if they can be robust enough to give you quality results." This raises a pressing question: what happens when machines no longer need human commands, but execute creative decisions on their own? At that point, AI might truly enter the last privileged domain once reserved for humans: creativity itself.

Humans have consistently delegated actions throughout history for efficiency, profit, food, shelter, or defense. This continuous implementation of technology for efficient labor has reshaped our engagement with the world in creative ways, now encapsulated in aesthetics informed by automation and machine learning, giving rise to metacreativity.

Sabrina Raaf's robot, Grower, serves as a powerful commentary on this global delegation of creative labor. The term "robot" itself, derived from the Czech "robota" (forced labor) and the Slavic "rab" (slave), underscores the historical implications of repetitive work. Factory workers, often forced into monotonous jobs due to limited options, exemplify this. Grower strips repetitive work to a simple algorithm: draw a line based on CO2 levels. Its slow, deliberate pace aestheticizes labor, turning it into a performance that comments on human power dynamics and our reshaping of nature for "efficiency." The longer lines, indicating higher CO2, metaphorically represent our destructive relationship with the environment, where higher "grass" (growth) signifies harm.

Grower reflects on the aestheticization of a fundamental aspect of labor that Braudel observed: human physical limitations. He argued that when human labor becomes costly, replacing it with machines becomes necessary. Artists, like researchers, constantly strive for productivity and quality. Grower guarantees a "creative product," yet Raaf, not the machine, is the artist—for now. This distinction may blur as selective creative processes are increasingly delegated to ML algorithms.

Understanding labor's role in creative practices is crucial for fair evaluation. The inherent physical connotation of "labor" often leads to art being undervalued economically. Measuring an artist's labor, much of which involves constant exposure to the world, is difficult. This complexity of aesthetics is a huge challenge for AI development. Current self-learning algorithms are designed for single, efficient actions, aiming for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), which mimics human-level intelligence.

Metacreativity thus emerges as the delegation of creative labor to self-training algorithmic machines. As ML frees humans from repetitive tasks—even playing musical riffs—to focus on broader creative issues, it also pushes humanity to redefine its identity. This mirrors political negotiations of human identity amidst economics, culture, and society. Sampling's cultural relevance, for instance, comes from human compromises in evaluating the world, often driven by a collective desire to control the uncontrollable—like nature. In this light, ML is the latest manifestation of humanity's ongoing quest for control.

Humans seek to dominate everything through our ability to turn materiality into modular pieces optimized to remain remixable. Labor, the very process through which this takes place, paradoxically, is subjected to itself: it is, after all, a set of executable actions. Remix when implemented with ML, as part of the paradigm of metacreativity, exposes, even more, the contentions between aesthetics and labor; particularly as selective processes that in the past have been exclusively performed by humans. Selectivity pushes creativity and remix against each other to reposition labor as a non-human action, an algorithm delegated to be performed by computers.